Tower Hamlets Cemetery Park is one of my favourite cemeteries to research and explore.

It doesn’t have the sepulchral magnificence of West Norwood, neither the romantic decay of Highgate, but out of the so-called Magnificent Seven of London, its the lower classes who are predominantly buried here and its their stories that I find more gripping than that of Lord and Lady Hobknob.

Today it is a woodland oasis, frequented by dog-walkers and people making use of the tranquil nature of the space. But to step back in time more than a century ago, you would have found yourself in the clatter of funeral carriages, grave diggers and never-ending mourners. This cemetery was BUSY. For my tours here last year I delved into the archives to see just how busy this now tranquil collection of trees and graves once was.

The Tower Hamlets of the 19th century was a place that experienced enormous social change in a very short space of time. From a rural backwater to suddenly housing thousands upon thousands of people as the land was redeveloped for housing on an massive scale and the proximity of London’s docklands welcomed people from all over the empire. Little distinction was made between residential and industrial, people would often live next door to turtle abbatoirs and blacking factories, which made it a dirty, odious place to live.

Death As a Part of life

But how did the cemetery operate amidst all this? With densely packed housing and diseases such as scarlet fever and cholera running rife, by the mid-19th century Bow Cemetery (as it was then known) was already known for being an epicentre of death – 1/7th of all London’s dead were being buried within its confines by 1867.

Wanting to explore this further, I randomly selected a year, a month and a day to see how Tower Hamlets Cemetery park used to function. Although this is just one day from its active history between 1840 and 1966, this deep-dive will illuminate just how active London’s busiest cemetery of the time used to be.

Monday 11th November 1872

The Southern Reporter comments on snowfall on this day 148 years ago and a letter to the Times comments on the ‘exceptional rainfall’ that happened earlier in the week. Either way, it probably would have been cold, damp and almost certainly dangerous to gravediggers who seldom had respite from the demands the local area commanded on them to make space for its cockney dead.

1/7th of all London’s dead were being buried within its confines by 1867

The archives, split between a daybook of private burials, pauper burials and then the register of private graves, are where we source the burial information from. The daybook, which is a unifying summary between the private and pauper register, show that funerals happened on most days of the week – although some days none were recorded. Whether this was because they needed ‘rest days’ to ready more of the grounds for burials, or, as I suspect, the administrator fell behind with keeping all the books in order, as I found in 1886 whilst researching Matilda Calverley, we cannot be sure.

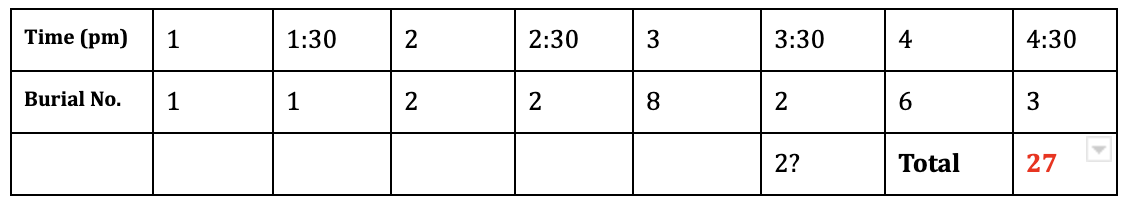

Funerals tended to happen in the afternoon between 1 and 5pm. The numbers of burials ranged from between 3 and 35 (35!) funerals a day, with the winter months unsurprisingly being much busier – and this is seen in other cemeteries of the time, such as Brookwood. Mondays tended to be the busiest days. Monday 11th November, my choice of a sample, saw 27 burials alone in a single afternoon.

The coffins would be scheduled for a certain time, and then arrive, together, for a service to be conducted in the (sadly, long demolished) chapel. Here are the breakdowns of the funerals and times that they happened on this particular day:

The size of the site probably allowed these to happen without too much disruption but even so – eight funerals starting at 3pm. Mind-boggling.

Looking at the names and then, the ages of those buried that day – gives an interesting snapshot into death and its affect on the local community and highlights that this, clealry, was another time. The death effect that COVID-19 is having on our localities chiefly, although not exclusively, targets the old. Samuel Thomas Pierce of 22 Middelton Road Bethnal Green – the presentation of name and address presumably that of an adult – was 4 years old. Mark Allan of Chrisp Street, Poplar, was only 9 hours old. 70% of those buried on this wet, cold, miserable day in November 1872 were children. Only two of the 27 in this sample – grown men, of 26 and 60 – went into private graves: the rest into communal plots, chiefly L551 or M136.

How does this compare to other cemeteries?

Contrast this to Brompton Cemetery, which catered to a more affluent class of the dead at the other end of the District Line in West London, which had 11 burials on the same day. Only 2 of those were under the age of 5 (18%), with the rest being adults (although most did go into common graves). Brompton is a a good cemetery for us to compare it with because in the 1860’s-1880’s it was considered the second busiest cemetery in London, after Tower Hamlets.

The level of death seen here did not continue. Bar a few instances, and the First World War when scores of the ‘unidentified’ were buried from the bomb sites that pock-marked the East End, the registers shows a smaller, older contingent being added to this place of memory. 80 years later to the day after my initial sample in 1952, it only took one burial: 68 year old William Stanley of 31 Arnold Road, Bow, who was placed into R5797.

By this time, better healthcare, the rise of cremation as an alternative to ye olde burial, as well as the cemetery approaching capacity, gives a very different picture as to how it operated a century before. It’s also interesting to note that the local MP, Charles Hay Ritchie, directly addressed concerns over the amount of Eastenders being buried here a decade afterwards in the 1880s after a damning Home Office report was sparked by complaints from local people.

I list the names of those 27 people: power is gained from stating these names in regards to reclaiming their history, but also as an invitation for you to go off and see what you can find out about them:

| Surname and Name |

Abode |

Sex |

Age |

Time of B |

Grave |

|

Nicholls, Henry Swain |

Lea Bridge Road, Walthamstow |

M |

60 |

3 |

Sq 57, 3033 |

|

Barrett, David |

22 Middleton Street, Bethnal Green |

M |

26 |

4 |

Sq 33/25, 4248 |

|

Pearce, Samuel Thomas, |

14 Warner Place |

M |

4 |

2 |

L551 |

|

Hudson, Henry |

Prospect Place |

M |

14 weeks |

3 |

L551 |

|

Merton, Robert |

1 Axe Place, Hackney |

M |

1 month |

4 |

L551 |

|

Munday, Maria Joyce |

32 Longfellow Road, Stepney |

F | 32 |

2 |

M136 |

|

Bryant, Mary Ann |

23 Delph Street, Bermondsey |

F |

3 |

3 |

M147 |

|

Willett, Thomas Alfred |

23 Ernest Street, Bermondsey |

M |

5 months |

3.5 |

L549 |

|

Urn, Joseph Piper |

8 Roswell Street, Bow Common |

M |

18 |

4 |

M146 |

|

Daniels, Mary Frances |

9 Paternoster Row, Spitalfields |

F |

2 |

3 |

L551 |

|

Peters, Esther |

25 Kent Street, Borough |

F |

72 |

3 |

M136 |

|

Wright, Sarah Louisa |

9 Cannon Place, Stepney |

F |

57 |

3 |

C390 |

|

A stillborn of Mrs. Argent |

Union Street, Stepney |

3 |

L551 | ||

|

Allan, Mark |

Chrisp Street, Poplar |

M |

9 hours |

L542 | |

|

Good, Alice Jane |

7 Alderney Street |

F |

2 |

2.5 |

L551 |

|

Feeney, Henry |

42 Lower Shadwell |

M |

1.5 |

1 |

L542 |

|

Briffett, John Charles |

Guys Hospital |

M |

16 months |

3 |

L551 |

|

Field, Walter Frederick |

5 Mansfield Cottages, Kingsland |

M |

3 months |

3.5 |

L551 |

|

Groom, Sarah |

15 Geo Street, Bethnal Green |

F |

11 months |

4 |

L551 |

|

Sears, Thomas |

Bethnal Green Workhouse |

M |

45 |

4.5 |

M147 |

|

Bull, Ethel |

Dock Cottages, Poplar |

F |

2 |

2.5 |

L551 |

|

Clark, Margaret |

12 Suffolk Street, Bethnal Green |

F |

19 months |

4 |

L551 |

|

Bishop, Sarah |

5 Sugar Loaf Court, Goodman’s Fields |

F |

20 |

4.5 |

M136 |

|

Middelton, James |

22 East India Road, Limehouse |

M |

49 |

2 |

C386 |

|

Smith, William Watthew |

Samuel Street, Limehouse |

M |

18 months |

4 |

L549 |

|

Musson, William John |

Burgess Street, Stepney (died in Children’s Hospital) |

M |

4 |

4.5 |

L551 |

|

Powell, Frances, Helena |

9 Princes Court, |

F |

2 |

L551 |

The next time you walk through Tower Hamlets Cemetery Park, remember the quietness of today is a world away from how active this space was 100 years ago. An epicentre of death to the local community: we only know a fraction of the social history that the cockney forefathers buried here lived and died through.

My thanks to Robert Just in providing age clarification on his great-great grandmother, Maria Joyce Munday.

References & Further Reading

‘London Cemeteries’, The Era, 17 Nov 1867, p.15, The British Newspaper Archive [online database], accessed 27 October 2020.

‘The Weather’, Southern Reporter, 14 Nov 1872, The British Newspaper Archive, [online database], accessed 27 October 2020.

‘Exceptional Weather’, Central Somerset Gazette, 9 Nov 1872, The British Newspaper Archive, [online database], accessed 27 October 2020.

City of London & Tower Hamlets Cemetery Register, 1868-1883, AncestryUK [online database], accessed 26 October 2020.

‘The Bow Cemetery Grievance’, The East London Observer, 9 Dec 1882, The British Newspaper Archive, [online database], accessed 21 January 2021.

A. Herman, Death has a touch of class, Society and Space in Brookwood Cemetery, 1853 – 1903, The Journal of Historical Geography, vol 36, p. 305 – 314.

Brompton Cemetery Register, 1873 Oct 24 – 1874 Mar 06, Ancestry UK [online database], accessed 26 October 2020.

3 responses to “A Day in the Death of A Cockney Cemetery”

[…] were 23 other burials that day (it was a busy cemetery, as I’ve researched before) and whereas the large majority of people buried there were locals hailing from Poplar, Stepney and […]

Thank you for this fascinating post. I can add some information on one of the burials that day. Maria Joyce Munday of Longfellow Road was my great-great-grandmother. She was actually in her early 30s when she died – there must have been an error or an illegible entry in the cemetery records. Her husband followed her in death later that decade, leaving my great-grandmother (age +/-13) in the care of the Mile End Old Town Workhouse at the time of the census of 1881. Her story underlines the general difficulty of life and immediacy of death for East London residents at that time. Annie Munday went on to live with a family in Holland Park (working as cook), then settle in Wandsworth. She had six children of her own, including my grandmother (who left London for New York). This is all information I learned only recenlty, partly via your blog post. Thank you!

Amazing! Happy to have been a part in exploring your family tree and bringing Maria’s legacy into focus!