One suspects that William Hogarth would chuckle bitterly at the irony – his home in Chiswick, once his peaceful country retreat, now backs onto a hellishly busy road and a concrete road junction named the “Hogarth Roundabout”.

It’s an incongruous backdrop to the quiet elegance of Hogarth’s house, which today is home to a lovely museum about the great artist’s life. Skilled as he was at portraying the vices, double standards and corruption of Georgian London, Hogarth would undoubtedly have found something to lampoon about the concrete hell of the modern, traffic-choked city. (Incidentally, cartoonist Martin Rowson did produce a homage to Hogarth using the roundabout as a centrepiece.)

However, just south of the Hogarth Roundabout the scene changes dramatically. The concrete gives way to a cluster of pretty Georgian houses, and the historic brewery of Fuller, Smith and Turner. It is against this rather quaint backdrop that you’ll find Hogarth’s eternal resting place, in the churchyard of St Nicholas, Chiswick.

By the time of his death in 1764, Hogarth was a well-respected artist – a satirist, painter, printmaker, engraver and cartoonist – and patron of many charities. Although he and his wife Jane never had any children, they fostered foundling children and were patrons of the Foundling Hospital in London. Starting life in Clerkenwell, Hogarth had a tough childhood.

By the time of his death in 1764, Hogarth was a well-respected artist – a satirist, painter, printmaker, engraver and cartoonist – and patron of many charities. Although he and his wife Jane never had any children, they fostered foundling children and were patrons of the Foundling Hospital in London. Starting life in Clerkenwell, Hogarth had a tough childhood.

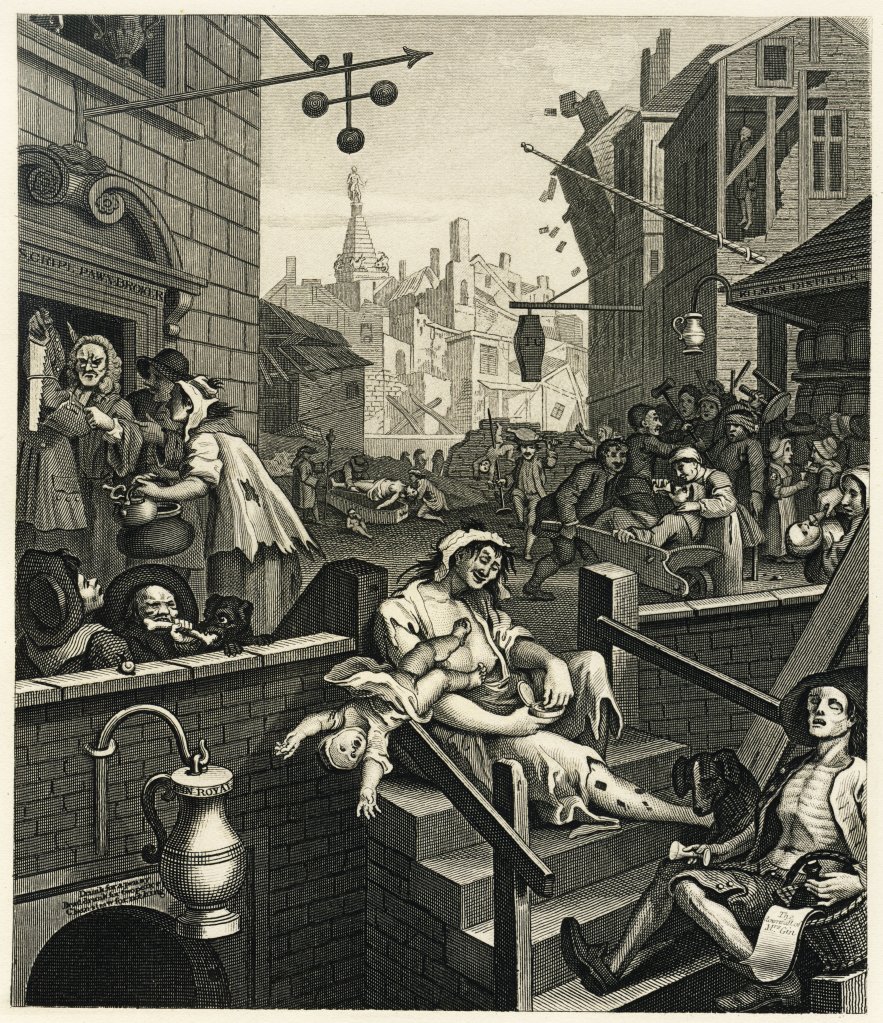

His father was imprisoned for debt. After beginning an apprenticeship as an engraver, Hogarth also turned his hand to painting and book illustrations. He produced many satirical images, most famously Gin Lane and Beer Street, and the “moral works” such as The Rake’s Progress and Marriage a-la-mode. His sharp eye for the ridiculous, the grotesque and the cruel made him famous and his images are those which we associate most closely with Georgian London even today.

But enough of his life, I hear you say. This is Cemetery Club, after all. So we will return to Hogarth’s final resting place, beneath a handsome memorial that befits a famous artist. Look a little closer at the tombstone, and you’ll find symbols relating to Hogarth’s life – the artist’s palette and paintbrushes, the oak leaves which often symbolise endurance and long life (Hogarth lived to be 66, not a bad innings at the time), the book which can be interpreted as showing someone’s accomplishments in life, and the mask which symbolises drama. The laurel wreath represents the “evergreen” memory of the deceased.

Hogarth’s friend, the actor David Garrick, provided an eloquent inscription for his tomb:

Hogarth’s friend, the actor David Garrick, provided an eloquent inscription for his tomb:

-

Farewell great Painter of Mankind

Who reach’d the noblest point of Art

Whose pictur’d Morals charm the Mind

And through the Eye correct the Heart.

If Genius fire thee, Reader, stay,

If Nature touch thee, drop a Tear:

If neither move thee, turn away,

For Hogarth’s honour’d dust lies here.

Hogarth’s tomb was restored in 2010. The stone was cleaned and the worn inscriptions were renewed, allowing visitors to the grave to once again be able to read Garrick’s tribute to his illustrious friend. An information panel was also installed nearby with details of Hogarth’s life and work.

Hogarth’s tomb isn’t the only one in St Nicholas’ churchyard that’s grand enough to warrant being fenced off with railings. An intricately-carved chest tomb stands nearby, remarkably well-preserved despite being over two hundred years old.

Hogarth’s tomb isn’t the only one in St Nicholas’ churchyard that’s grand enough to warrant being fenced off with railings. An intricately-carved chest tomb stands nearby, remarkably well-preserved despite being over two hundred years old.

Richard Wright, the man commemorated by this superb memorial, was a bricklayer. Not any old brickie, though – he was the bricklayer to Lord Burlington, owner of the nearby Chiswick House. Chiswick House, designed by William Kent and completed in 1729, was an early example of Palladian architecture in Britain. William Hogarth was a scathing critic of the Palladian style, seeing it as unpatriotic.

Richard Wright, the man commemorated by this superb memorial, was a bricklayer. Not any old brickie, though – he was the bricklayer to Lord Burlington, owner of the nearby Chiswick House. Chiswick House, designed by William Kent and completed in 1729, was an early example of Palladian architecture in Britain. William Hogarth was a scathing critic of the Palladian style, seeing it as unpatriotic.

Wright’s tomb showcases some symbols commonly seen on 18th Century tombstones. Cherubs were an extremely popular motif in this period, and can be seen in a great deal of art and decoration as well as gravestones.

And then there’s the skull and crossbones. The hollow eyes of the twin skulls, one on each side of the monument, still stare out from the tomb in a sinister manner. To our modern sensibilities, it seems dreadfully morbid to feature skulls on the grave of a loved one, but in the 17th and 18th Centuries memento mori images were very popular.

And then there’s the skull and crossbones. The hollow eyes of the twin skulls, one on each side of the monument, still stare out from the tomb in a sinister manner. To our modern sensibilities, it seems dreadfully morbid to feature skulls on the grave of a loved one, but in the 17th and 18th Centuries memento mori images were very popular.

Another common memento mori symbol found on Georgian graves is the hourglass – a symbol of the inevitability of passing time. Again, rather an ominous choice, which reflects the gloom and austerity often present in Protestant thought at the time.

Another common memento mori symbol found on Georgian graves is the hourglass – a symbol of the inevitability of passing time. Again, rather an ominous choice, which reflects the gloom and austerity often present in Protestant thought at the time.

You’ll notice that none of these symbols are really the kind of symbols one associates with Christianity. Crosses and crucifixes are a common sight in Victorian cemeteries, but not on older graves. In the 17th and 18th Centuries, when anti-Catholic sentiment was still widespread, symbols such as crosses, crucifixes and images of Christ were seen as popish, so the symbolism we see on Anglican and Nonconformist graves in this period tends to be more secular, associated more closely with death than it is with Christianity.

You’ll notice that none of these symbols are really the kind of symbols one associates with Christianity. Crosses and crucifixes are a common sight in Victorian cemeteries, but not on older graves. In the 17th and 18th Centuries, when anti-Catholic sentiment was still widespread, symbols such as crosses, crucifixes and images of Christ were seen as popish, so the symbolism we see on Anglican and Nonconformist graves in this period tends to be more secular, associated more closely with death than it is with Christianity.

The 19th Century, on the other hand, saw the legal emancipation of Catholics, and the emergence of the Oxford Movement within the Anglican Church, which embraced many ideas inspired by Catholic symbolism and rites. The Gothic revival was also inspired by this resurgence in Catholic imagery and ideas, and many Victorian graves reflect this with angels, pinnacles, and crosses, as well as depictions of Christ and the Lamb of God.

Beyond the churchyard is another burial ground, Chiswick Old Cemetery, which was opened in 1871, after the churchyard was closed to new burials. To walk through the churchyard and then the cemetery really is to take a walk through time – you begin with the Georgian tombs close to the church, with their skulls and cherubs, through the Victorian angels and Gothic pinnacles, to the black marble and colourful windmills of modern gravestones.

Beyond the churchyard is another burial ground, Chiswick Old Cemetery, which was opened in 1871, after the churchyard was closed to new burials. To walk through the churchyard and then the cemetery really is to take a walk through time – you begin with the Georgian tombs close to the church, with their skulls and cherubs, through the Victorian angels and Gothic pinnacles, to the black marble and colourful windmills of modern gravestones.

St Nicholas’ Churchyard and Chiswick Old Cemetery are open to visitors every day during daylight hours.

4 responses to “William Hogarth and his neighbours in a Chiswick churchyard”

[…] talented Victorian illustrator and caricaturist: his skill had him regarded as a then modern-day Hogarth. He was initially a friend of the Tour-guide’s chum and all-round writing supremo Charles […]

[…] The Georgian graves clustered closest to the church (including the grand tomb of the artist William Hogarth) give way to Victorian and more modest headstones, filling a site that’s just under 7 acres […]

[…] Cemetery Club […]

Morning Caroline doing some family tracing research and being ex army I visit local grave yards, and take photos of military , not just official CWC graves but family ones. And all unusual graves . Would you like me to send any of the interesting one . I’ve take some in some of the cemeteries you have visited. There’s a great one in St Marys Mortlake Richard Burton the Spy and military man , he’s on the web. And taken many in old Chiswick cemetery including famous VC winner in the Zulu war ( well known film. Max