Life lived with a bang, ended with a whimper

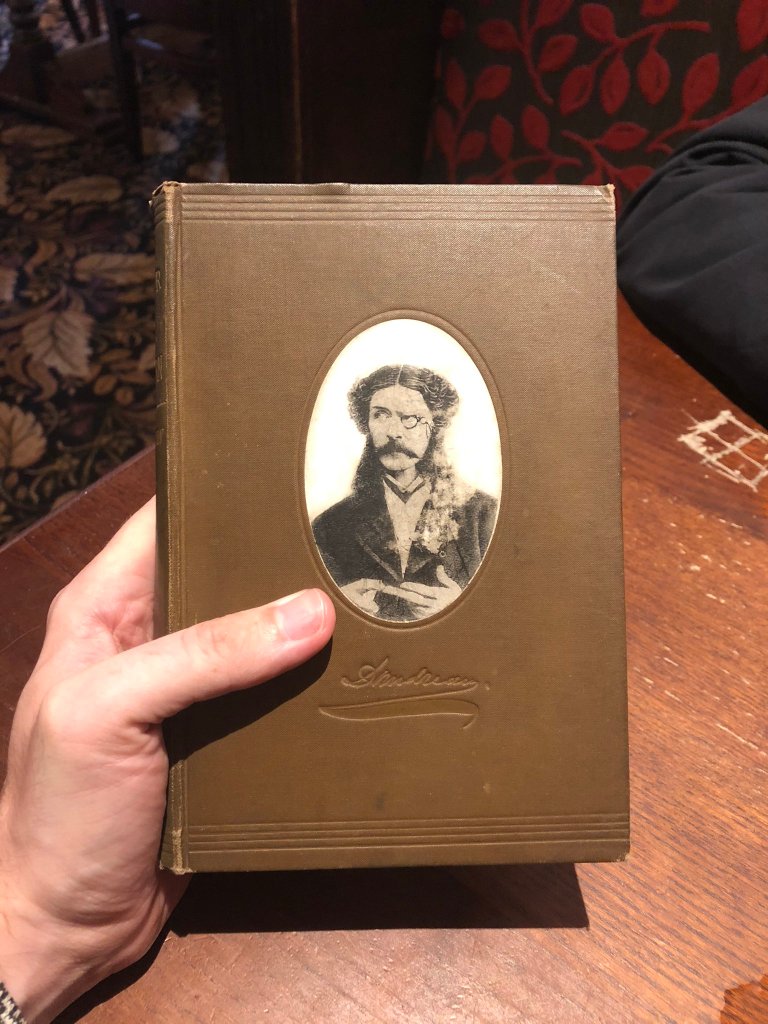

Look at the cover image on this biography, written by Thomas Edgar Pemberton.1 Dressed with long, theatrical whiskers and a quizzical, confused glance – this was an extraordinary gentleman, resembling a 19th century Tom Selleck, who commanded a fee of £235 a week2 (roughly £23,500 in 2024 money). His gift for pranks and jokes, and the fact his birthday wa son April Fools Day had many think his funeral wasn’t genuine.

Who was he?

Comedic actor Edward Askey Sothern, of course. He was son of a merchant and was born in Liverpool. Originally he studied medicine but was disgusted at a dissection he saw at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital. He got a job as a clerk in a shipbroker’s office in the city of his birth, before making his amateur debut on the stage in Jersey under the name of Douglas Stuart in 1849.3

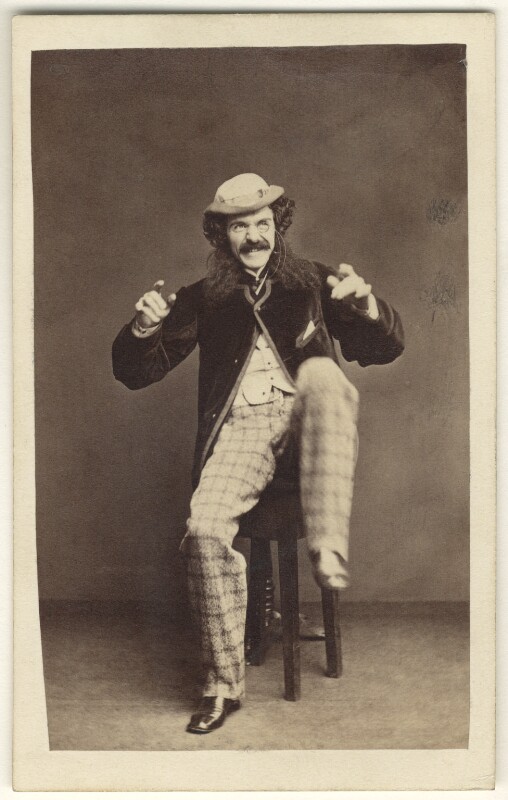

Performing in cities such as Birmingham, Portsmouth and Wolverhampton, he tried to break in America in the manner of a Romeo, to woeful reviews. When he got a part in Tom Taylor’s Our American Cousin, he played a role that would define his career. The play was the one Abraham Lincoln was watching as he was assassinated (although Sothern wasn’t in the cast that night in 1865), he was portraying Lord Dundreary, a role that only had forty seven lines. Sothern, clearly thinking ‘sod it, what the hell!’ ran with the character and emphasised the worst attributes of dandy Victorian fops, from their lisps, walks and mannerisms.

Sothern was reluctant to do the part at first. ‘It’s a rather small part’ he worried, only to be told by a fellow actor Joseph Jefferson that ‘there are no small parts, only small actors’.4

By the end of the decade the character became synonymous with excess and nonsense. It gave rise to ‘dundrearyisms’ – malaporprams after Sheridan; muddled sayings such as ‘birds of a feather gather no moss’. He’d also play Dundreary’s brother Sam in a short-lived production written by John Oxenford. Such was his commital to Dundreary’s pecularities that a stutter he affected for the role took him years to shake off – a historical precence of Tim McInnery and his eye twitch for Captain Darling in Blackadder. Fashion followed his vogue, with shops selling Dundreary-related fashions and stylings.5

He would later have another role as 18th century actor David Garrick in Thomas William Robertson’s play of the same name. A very different role from Dundreary, the critics weren’t hugely impressed with it in the shadow of the lisping aristocrat, but the audiences devoured it. His friend, Edward Matthew Ward, painted him in the role in a piece that is now part of the Tate collection. Ward’s son Leslie would go on to have notoriety of his own.

Sothern loved nothing more than to irritate and rub people up the wrong way for a laugh. He remarked the best lines of dialogue from David Garrick came from him, rather than Robertson. Robertson, the playwright (understandably) was not best pleased with this.

The Practical Joker

Sothen belonged to a group who pranked others relentlessly. One evening he was dining with actor-manager John Lawrence Toole and panicked the waiter by tossing the cutlery out of the window and then hid under the table, to make it look like they’d dined and dashed. When the waiter returned, both men were eating happily, as if nothing had happened.

When he wasn’t acting he was hunting; much to the annoyance of theatre managers. He’d be off on a horse somewhere in Leatherhead or Windsor and have a performance at a theatre such as the Haymarket that afternoon. On one occasion he had to bribe a train driver at Three Bridges to divert a locomotive to Clapham Junction to ensure he wouldn’t miss a performance.

Sending letters was also something he revelled in. Many of his recipients would find their letters sent from his house in Chelsea with postmarks from Dundee, Glasgow, Dublin and the Suez Canal – with no explantion as to why. He would intially write an address on the envelope in pencil and send it on as normal, asking the receiver to send it back to him. He would then recycle the envelope, before sending it on to someone of high importance. One wonders how much time he had at his disposal.

Another incident involves a visit to an ironmonger. Accompanied by a friend, he walks in and asks for ‘Macaulay’s History of England‘. Confused, the shop assistant directs him to the booksellers just down the road. But Sothern wanted it gift wrapped: the assistant asserts once more that it’s an ironmongers and not a book shop. “I’m in no hurry. I’ll wait here while you reach it down.” The manager is then called for by his frantic employee, at which point Sothern calmly asks for ‘a small, ordinary file, about six inches in length’. The manager shoots a look of ‘supreme disgust’ at his assistant and Sothern’s friend can barely contain herself.

The Death

Sothen was due to perform in a play written by William S. Gilbert entitled Foggerty’s Fairy, which had concepts that would weirdly be seen in Back to the Future over a century later. How one event in the past can be changed to influence the present.6 No flux capacitors, but a fairy called Rebecca.

He had returned to England for a six week holiday to discuss the project (which was written for him especially) but ongoing script issues prevented sooner production.He wasn’t in the best of health. Battling a chest compliant he’d picked up in New York, he died at his residence in Vere Street, Cavendish Square and was buried in Southampton Old Cemetery, as per his own request, to be with a sister who predeceased him. His name, shown on what’s actually the back of the monument, simply describes his output as ‘comedian’. It was designed a smaller imitation of Adelaide Neilson’s cross in Brompton Cemetery.7

For such an extrovert, his end is jarringly lonesome and quiet. His burial was attended by only a few, those who believed he was actually dead, and his will, changed last minute in favour of his sister and cutting out his wife and his son, Lytton, who had already received more than enough [sic], still puzzles historians today. He left not with a bang, but a mousy, retiscent whimper.

Someone who once staged a slanging match with a friend on a busy omnibus and would be ‘forever remembered’ by his biographer, seems to have ostracised himself and been largely forgotten in death.

References & Source Material

- Templeton, T. E, A Memoir of Edward Askew Sothern, (London, Richard Bentley & Son, 1890) ↩︎

- Thrupp, Birmingham, Edward Askew Sothern, actor, AbeBooks, https://www.abebooks.co.uk/photographs/Thrupp-Birmingham-Edward-Askew-Sothern-actor/30636126984/bd, accessed 1 Mar 2024 ↩︎

- Holder, Heidi J., Sothern, Edward Askew, The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (14 Oct 2021), https://www.oxforddnb.com/display/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-26040, accessed 1 Mar 2024

↩︎ - Ibid. ↩︎

- Sims, George R, My Life: Sixty Years’ Recollections of Bohemian London, (London, Eveleigh Nash Company, 1917), p. 93. ↩︎

- Cole, S, Foggerty’s Fairy, The Gilbert & Sullivan Archive, (Jan 1993), https://www.gsarchive.net/gilbert/plays/foggerty/foggerty.html, accessed 1 Mar 2024 ↩︎

- Memorial to Sothern, Manchester Courier, (1 Sept 1894), p. 13, The British Newspaper Archive, https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000206/18940901/170/0013, accessed 1 Mar 2024. ↩︎